The Mind and Intellect

11/10/2023

Finding Balance or Being Centered – What’s the Difference?

08/11/2023

Banking Before Coinage

Banking is one of the oldest economic activities in human history. It existed long before coins were invented. Ancient civilizations used various forms of trade, credit, and wealth storage—even thousands of years before coinage appeared.

Coinage Sparks a Need for Bankers

In the 7th century BC, the Lydians introduced coins. The Greeks quickly adopted and expanded this innovation. Each Greek city-state, or polis, began minting its own coins to assert political independence. This flood of diverse currencies soon overwhelmed markets. Many coins differed in weight, denomination, and purity. Some were even counterfeit. A system was needed to restore order.

The First Professional Bankers: Trapezitai

In 6th-century BC Greece, the first professional bankers emerged. Known as trapezitai (from trapeza, meaning table), they worked at money-changing tables in public markets. Initially, they tested coin purity and exchanged different currencies. Over time, their role expanded. As their reputation grew, people began depositing money with them for safekeeping. These moneychangers gradually became full-fledged bankers.

Banking Rooted in Ethics and Trust

Banking success in ancient Greece depended on trust. Ethical standards and personal integrity were essential. People entrusted their assets only to those bankers known for honesty. Without that trust, banking would have never taken root.

The Bank: Trapeza in the Agora

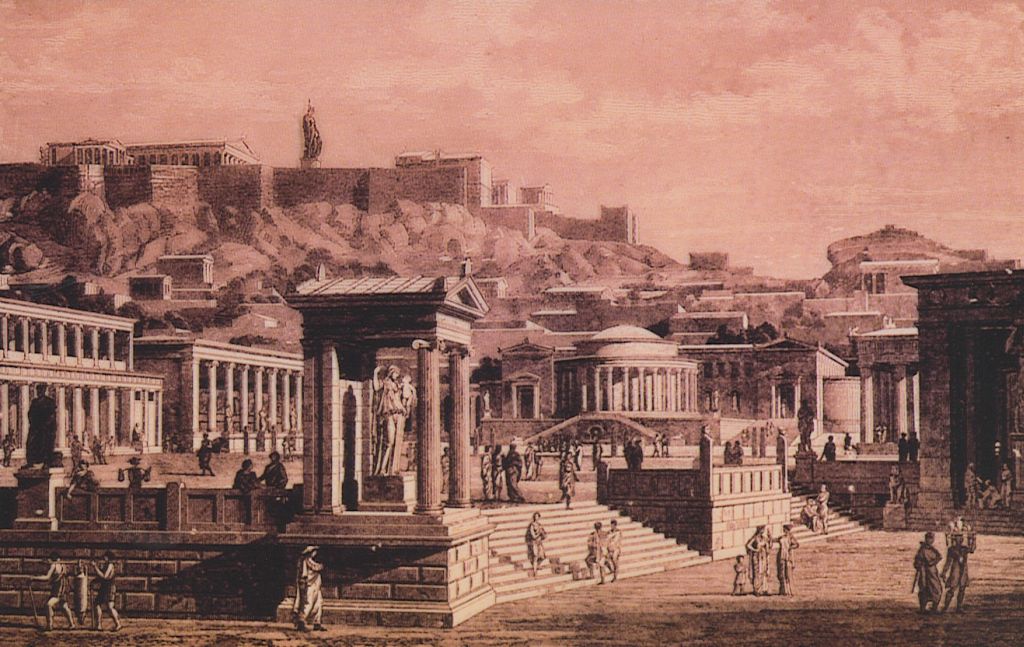

Greek banks (trapezai) were located near the agora—the economic and cultural heart of every polis. These were solid, secure buildings designed to conduct financial operations and store valuables. Proximity to the marketplace ensured easy access for clients and merchants.

Ancient Greek agora or marketplace was a place of social gatherings and various business transactions

Tools of the Trade: The Touchstone

To verify the purity of precious metals, bankers used a touchstone—a small, smooth, black stone. By rubbing a coin against it, they left a streak of metal. They compared this to known streaks of pure gold or silver to determine authenticity. This simple tool helped prevent fraud and ensured fair trade.

Structure and Personnel of Ancient Banks

Each trapeza was owned and operated by a free Greek citizen. However, daily operations involved a team of assistants—usually well-trained slaves or freedmen. Their number and responsibilities varied depending on the size and scope of the bank. Interestingly, these workers often held significant status in business circles.

Key Functions of Early Greek Bankers

Greek bankers went beyond coin testing and currency exchange. Their services quickly expanded to:

- Accepting deposits

- Providing loans at interest

- Safekeeping valuables

- Managing assets for wealthy clients

Lending became the core function. Most loans charged an annual interest rate of around 12%. However, maritime loans—used for high-risk sea trade—often carried interest rates between 12% and 100%, depending on the route and season.

Securing Loans with Valuable Collateral

Loans were usually backed by collateral. Wealthy clients offered real estate, merchant ships, slaves, or mining operations to secure financing. The type of collateral depended heavily on a borrower’s social class and assets.

Social Mobility Through Banking

Contrary to modern assumptions, slaves in ancient Greek banks often held influential roles. Many earned their freedom through manumission or inheritance. These opportunities allowed them to rise socially—making them some of the most mobile and economically active individuals in Greek society.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Trust and Innovation

Ancient Greek banking laid the foundation for many practices still in use today. With a focus on trust, practical tools like the touchstone, and sophisticated loan structures, Greek trapezitai helped shape the modern concept of professional banking.